Cham-Ber Huang - CBH 2016

Information and photographs on this page, courtesy of the late Danny Wilson, Bass harmonicist with The Dave McKelvy Trio, Jerry Murad's Harmonicats, and Executive Vice President Emeritus of SPAH Inc. One of the finest bass harmonica players of his time.

The following are two articles that appeared in DuPont publications in 1975, heralding the introduction of Cham-Ber Huang's revolutionary harmonica design. Even though Mr Huang eventually left M Hohner Inc to form his own harmonica manufacturing and distribution company, the articles are reprinted here for their historical significance, and for the edification of all who wish to benefit from them. Bear in mind the articles are dated, and references to cost and time frames reflect the date of publication. Also, as they are reprinted from trade journals, they are weighted toward the technical aspect.

Article reprinted from Engineering Design with DuPont Plastics, Spring 1975 issue:

HOHNER CREDITS ADDED VOLUME AND RESONANCE, SMOOTHER SLIDE ACTION OF THE "CBH" TO TWO "DELRIN" RESINS

Hicksville, Long Island, New York

If you can memorize the musical scale, you can play the harmonica. Blow into the proper hole and you've sounded "do"; draw out and you'll produce "re". Repeat the exercise at the next two holes, reverse it on the fourth and you will have run through a complete octave. With a few hours of practice, you'll be playing "Oh Susanna" or "Home on the Range" and, someday, maybe even "Peg O' My Heart".

Not surprisingly, an estimated 50,000,000 Americans have gotten at least that far on what may be the world's most popular instrument, the Hohner "Marine Band". On more sophisticated models, multi-reed chromatic harmonicas that include sharps and flats played in the same fashion, but with the aid of a simple finger slide, a few have even scaled artistic heights.

Familiar names in that category include concert virtuosos Larry Adler and Richard Hayman, the two John Sebastians, Senior and Junior (the latter of "Lovin' Spoonful" fame), Bora Minnevitch (sic) of the "Harmonica Rascals" and Cham-Ber Huang, who has won international acclaim as a technician and interpreter of classical and baroque music as well as for his complete redesign of the versatile woodwind.

Woodwind (or brass) could be a misnomer for the instrument that carries Huang's imprint, even to the inclusion of his initials in its trademark -- the Hohner "Professional 2016 CBH". While retaining the hand-tuned bronze reeds traditionally associated with Hohner, the body, slide assembly, mouthpiece and face plates of this new harmonica are all injection molded in "Delrin" acetal resin. What's more, it's these molded components that are responsible for the special benefits of this model -- the fastest playing speed ever attained on a harmonica, smoother slider action and quick response, added volume and resonance.

Outstanding features of the "CBH" and probably the most important of its 18 patented innovations are (1) a half-round, non-stick slide of "Delrin" AF, a resin containing "Teflon" TFE fibers for high resistance to abrasion and wear, and (2) molded-in resonating chambers -- 16 on each side of the harmonica body, 32 in all -- which take advantage of the dimensional stability of glass-filled "Delrin" 570.

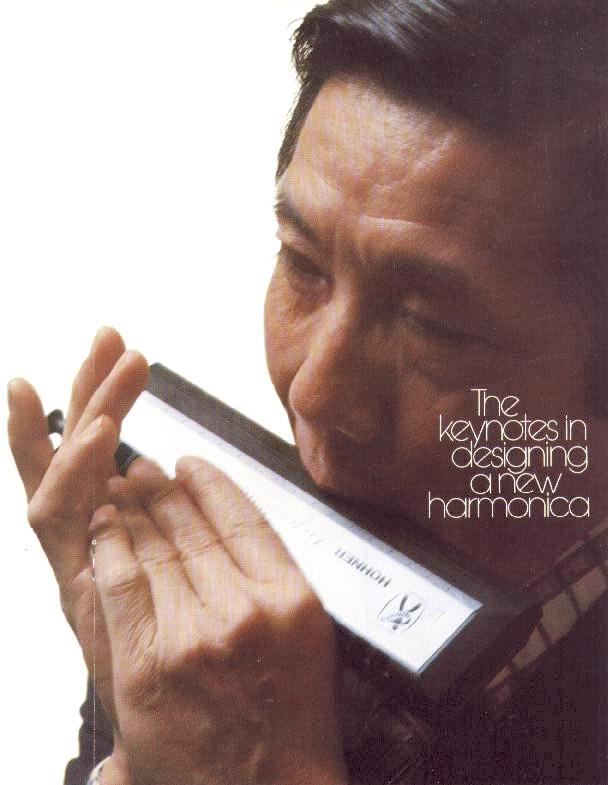

Notched, half-round slide, molded to a tolerance of .001 inch in "Delrin" AF, was designed to glide freely in the groove atop the body of the Hohner "CBH" harmonica, yet eliminate air leakage between chambers. When the spring-return plunger is depressed -- as in the hands of inventor Cham-Ber Huang -- lever (arrow) moves slide to channel air against reeds that sound sharps or flats.

The new instrument is the product of a 40-year love affair that began when Huang purchased a "Marine Band" in his native Shanghai. Though he holds dual degrees in music and engineering, his career has revolved entirely around the harmonica in his roles as both a performing artist and chief of research and development for German-based M. Hohner, Inc. Archtype of the "CBH" is a hand-made silver harmonica that Huang carried with him two years ago when he returned to China for a guest appearance with the Central Philharmonic Orchestra of Peking as part of a cultural exchange program.

"It's still my favorite," says Huang, blowing a tremulous chord on the shiny but bulky instrument. "It's hand-machined and its notes are as clear as a bird call. But precision machining cost more than $5,000 and reproducing it in any metal would be prohibitive in terms of money. What's more, it weighs 45 ounces and it gets kind of tiring when you've been holding it onstage for a half hour or more."

Not so with the "Professional 2016 CBH". A 16-hole instrument whose 64 reeds cover a four octave range, it weighs a light 11 ounces. And its price, though considerably higher than most other Hohner harmonicas (the "Marine Band" has an under-$6 tag) is only $59.95.

"Weight and cost reduction are two of the benefits we derive from 'Delrin'," Huang notes. "Its main contributions, however, are its quality surface characteristics -- its low coefficient of friction, its smoothness and appearance -- and its strength."

Machinability played an important role in the prototyping of the "CBH" but the controlled shrinkage and close molding tolerance capabilities of "Delrin" -- less than 0.001 inch over the 6-5/8 inch-long slide -- have minimized requirements in this area.

Huang totally redesigned the slide -- a notched, flat metal blade in most previous models. As the slide glides back and forth in an accommodating body groove, a single notch links each of the 16 playing holes alternately with two of the 32 reed chambers (see photo). When a performer blows or draws at a specific hole, say Middle C, air is channeled directly at only one reed to sound either a perfect Natural C or D and, when the slide plunger is pushed in, C sharp/D flat or D sharp/E flat.

The 32 molded-in chambers -- 16 on each side -- of the "CBH" body or core (A) take advantage of the dimensional stability of glass-filled "Delrin" 570. The contoured mouthpiece (B) and the face plate or combs (C) benefit from its stiffness and smooth, even texture while the slide-actuating plunger (D), lever (E) and bushing (F) utilize its natural lubricity. Slide (G) is molded of "Delrin" AF. Only major use of metal is in the hand-tuned bronze reed plates (H).

"Our purpose was to eliminate the air leakage between chambers that can blur a note," Huang points out. "That called for an extremely tight fit but a free moving slide. In both the silver model and the plastic prototype we achieved it with a slide of 'Teflon' TFE fluorocarbon resin. But in the production model, we obtained equally good results with 'Delrin' AF. And at reduced cost with better stiffness. More important, the slide shifts in a fraction of the time required by a metal slide."

Friction-free motion is also essential in the spring-return plunger that actuates the slide, but the natural free movement of glass-filled "Delrin" 570 more than met the specifications. Glass-filled "Delrin" also contributed important stiffness and dimensional stability in attaining carefully calculated individual chamber shapes and volume in the 7-1/2 inch-long body section. Quick and accurate assembly was also assured.

There are other assets. The smooth, even texture of "Delrin" 570 in the contoured mouthpiece and face plates makes the "CBH" easy to hold and comfortable to play. Its strength, toughness and impact resistance make it virtually unbreakable in normal use. Resistance of the material to moisture assures smoother function of moving parts.

A Precision Instrument --

"It's a precision instrument," affirms Eugene Graber, president of Graber Rogg, Inc, Cranford, NJ, and one of a select audience of molding experts and technicians who heard the first performance on the "Professional 2016 CBH". It was Huang's rendition of the first movement of Bach's E Flat Major Sonata for the flute and it proved to be the "go-ahead" signal for the first production run.

"The original specifications called for the slide groove to be precision machined to .380 inch diameter so as to allow for the smooth movement of the .378 inch diameter slide," Graber recalls. "At Cham-Ber's request, we retooled the slide cavity to lower the clearance still further to .001 inch. When he came down to check the fit, he didn't bother with a micrometer or calipers. He just assembled the parts, screwed on two reed plates and began to play. When he kept on playing, we knew we had succeeded."

"There's just no other way to test a musical instrument," according to Huang. "The professional harmonica player couldn't care less about the dimensions of the instrument. What he's interested in is how fast and true it will play."

Article reprinted from DuPont Magazine, May - June 1975 issue:

A LITTLE CHAM-BER MUSIC

M Hohner, Inc, the Big Name in Harmonicas, Hits a New Note with "Delrin" Acetal Resin -- By George Neilson

Despite origins half a world and five thousand years apart, the harmonica and Americans seem to have been meant for each other. Today, more than 40 nations belong to the International Harmonica Federation, and call the instrument by such names as organa de boca, fisarmonica, and Mundharmonika. To most Americans, however, the mouth organ seems peculiarily their own, like six-guns, jazz, and hot dogs. It's easy to see why.

Introduced into the United States in the late 1850's, the harmonica became a welcome companion for people on the move in a vast, and often lonely country. It went with the pioneers in their wagons and with cowboys in their saddle bags. Soldiers in gray and soldiers in blue, huddled around campfires, sought comfort in its reedy tones. Generations of kids in small towns, city streets, and country lanes had their first musical experience with harmonicas. Even today, millions of harmonicas -- more than one-third the world's production -- are sold annually in the US. An estimated 20 million Americans know how to play the instrument, and there are more harmonicas in the country than all other instruments combined. Indeed, some people insist that it was America that discovered the mouth organ.

Actually, a Chinese emperor probably deserves the credit by inventing a wind instrument called the sheng around 3,000 BC. The sheng (which means "sublime voice") consisted of graduated tubes with free reeds set in a vessel with a single mouth piece. Nearly 5,000 years later, travelers from the Orient brought the sheng to Europe. And, in 1821, a 16-year-old watchmaker named Christian Ludwig Bushmann, probably inspired by the Chinese instrument, put 15 pitch pipes together and began producing music.

Another clockmaker, Christian Messner, acquired a Buschmann Mund-aeoline (mouth harp) and began making and selling the instruments to other clockmakers. One was purchased by 24-year-old Matthias Hohner, who, seeing commercial possibilities in large-scale production of harmonicas, set up his own company in Trossingen, on the edge of the Black Forest. In the first year of operation, Hohner, his wife, and two other workers turned out 650 instruments. Today, the Trossingen plant of M Hohner, Inc, produces more than that in one hour, despite the 50 separate hand operations required.

Not only has production soared, but different models have proliferated until today there are more than 50. Basically, the harmonica is diatonic; it plays only the notes registered by white keys on a piano, but not the sharps and flats achieved via the black keys. A skilled, experienced harmonica player can compensate for this limitation by "bending" the reeds to get the half notes; this is a principle on which the popular blues style is based. In the chromatic harmonica, a slide adds the missing half-notes. The smallest Hohner model is the "Little Lady", 1-3/8 inch long; the largest is the Chord Rhythm Harmonica, which is 21 inches long and has 1,276 parts. The most expensive harmonica, gold with brass reeds, was made for Pope Pius V. Two years ago, when Shanghai-born American virtuoso Cham-Ber Huang made a guest appearance with the Central Philharmonic Orchestra of Peking, he used a special, $5,000 silver instrument.

This year, M Hohner, Inc, is introducing a new model and Huang is its inventor. As a musician, he is the only concert harmonica artist listed in the prestigious music encyclopedia, Riemann's Musik Lexicon. As a teacher, Huang heads the harmonica department at Turtle Bay Music School in New York, and is on the faculty of Kingsborough Community College of the City University of New York at Manhattan Beach. As a technician, he is director of research and development for M Hohner, Inc, in Hicksville, NY.

Photo at left: Cham-Ber Huang leads members of his CBH Harmonica ensemble in a rehearsal session at the Turtle Bay Music School as Sissy Nitsch switches to the cello for the baroque number. The "Professional 2016 CBH" played by Huang, an internationally renowned interpreter of baroque and classical music, was designed by him in "Delrin".

The new Hohner model is the "Professional 2016 CBH", the initials identifying Huang as its inventor. It retains the hand-tuned bronze reeds of traditional harmonicas, but has been redesigned to incorporate improvements suggested by professional musicians in response to a Hohner inquiry. "They told us they wanted more resonance, more volume," says Huang. "They also wanted faster response and smoother action on the slide plunger. We achieved all these things, and more, by redesigning the parts and molding them from 'Delrin' acetal resin."

In previous chromatic models, the slide was a notched, flat, metal blade; in the CBH, it is half-round, and molded from "Delrin" AF, a resin containing "Teflon" TFE fibers for high resistance to abrasion and wear. "We wanted to eliminate the air leakage between one chamber and another that can blur a note," Huang says. "That called for an extremely tight fit, and a free-sliding motion. 'Delrin' gave it to us. The new slide shifts in a fraction of the time required by the old metal slide, and costs less to produce." Huang adds that "Delrin" is also vital for the friction-free motion of the spring-return plunger that actuates the slide.

In the CBH model, 32 resonating chambers are molded into a body of glass-filled "Delrin" 570. "It gave us the stiffness we needed in retaining proper dimensions in the complex body section, and in assuring quick and accurate assembly," Huang says. "It has other benefits, such as strength, toughness, and impact resistance that make it virtually unbreakable. Its resistance to moisture means that moving parts will continue to function smoothly. Its smooth, even texture in the contoured mouthpiece and face plates makes the CBH easy to hold, comfortable to play."

Ernest Graber, president of Graper, Rogg, Inc, molders of the CBH's parts, was in a select audience for the first performance of the new instrument as Cham-Ber Huang played the first movement of Bach's E-flat Major (Flute) Sonata to signal the first production run. "The original specification in the slide area had been plus-or-minus 0.002 inch," Graber recalls, "and at Cham-Ber's request, we retooled the cavity to lower it. When he came to check the fit, he didn't bother with a micrometer or calipers. He just assembled the parts, screwed on two reed plates, and began to play. When he kept on playing, we knew we had succeeded." According to Huang, "there's no other way to test a musical instrument. The professional harmonica player couldn't care less about dimensions. All he's interested in is how fast and how true it will play."

The "Professional 2016 CBH", now being produced in Hicksville, is the first Hohner harmonica to be produced in the United States. The company's other products -- keyboards, guitars, and other instruments and accessories -- are manufactured in plants throughout the world, but Trossingen remains the harmonica capital. Nearly every family there has at least one member working for Hohner; often jobs are passed from one generation to the next. Tuners, with an ear for perfect pitch, are very important people at the plant. They spend each day in small, individual rooms, listening to the sounds produced by a bellows drawing air across reeds, one by one, and making corrections where necessary. The town is the home of the State Music College of Trossingen, where harmonica, accordion, piano, and violin are taught.

Cham-Ber Huang regards the "2016 CBH" as an example of the harmonica's responsiveness to changing musical tastes. "Sure, you'll still find the mouth organ in the company of a fiddle and guitar at a country hoedown," he says, "but you'll also find it in concerts by the Rolling Stones and other rock groups. It's as much at ease in the hands of classical virtuoso John Sebastian, Sr, as it is in those of his son, leader of the now-disbanded 'Lovin Spoonful,' or in the hands of country and western star Charlie McCoy who was named instrumentalist of the year three times in a row."

Huang bought his first Hohner "Marine Band" harmonica in his native Shanghai when he was six years old, and taught himself to play it. His interest in the instrument continued as he pursued a degree in engineering at Shanghai's St John's University, and a degree in violin at the Shanghai Music Conservatory. In 1953, he arrived in New York and made his American concert debut with the harmonica at New York's Town Hall. Since, he has appeared in concerts throughout the world.

Despite his fame as a concert artist, Huang feels his greatest contribution to the art may be in his technical accomplishments. "I am very pleased to have my initials -- CBH -- engraved on the new '2016'," he says. "Incidentally, if anyone wonders about my first name -- Cham-Ber -- the explanation is simple. My surname is that of the first Chinese emperor, Huang, which means the royal colors of gold and yellow. When I was born my parents named me Tsing-Barh, meaning sky blue and crystal white, a combination that represents purity. After I left China, I felt this was all a little too colorful for most people; they had trouble pronouncing and spelling it. I wanted another name, and since my harmonica concerts generally fit into the musical category known as 'chamber music,' I injected a hyphen in the word to give it an Oriental flavor, and I have been Cham-Ber ever since."

Huang's affection for the harmonica is felt universally by those who have succumbed to its charm. John Steinbeck caught some of this in his Grapes of Wrath: "A harmonica is easy to carry. Take it out of your hip pocket, knock it against your palm to shake out the dirt and pocket fuzz and bits of tobacco. Now it's ready. You can do anything with a harmonica . . . you can mold the music with curved hands, making it wail and cry like bagpipes, making it full and round like an organ, making it as sharp and brittle as the reed pipes of the hills. And you can play and put it back in your pocket. It is always with you, always in your pocket." From the Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, copyright 1939 and 1967.

Information and photographs on this page, courtesy of the late Danny Wilson,

Bass harmonicist with The Dave McKelvy Trio, Jerry Murad's Harmonicats, and Executive Vice President Emeritus of SPAH Inc. One of the finest bass harmonica players of his time.